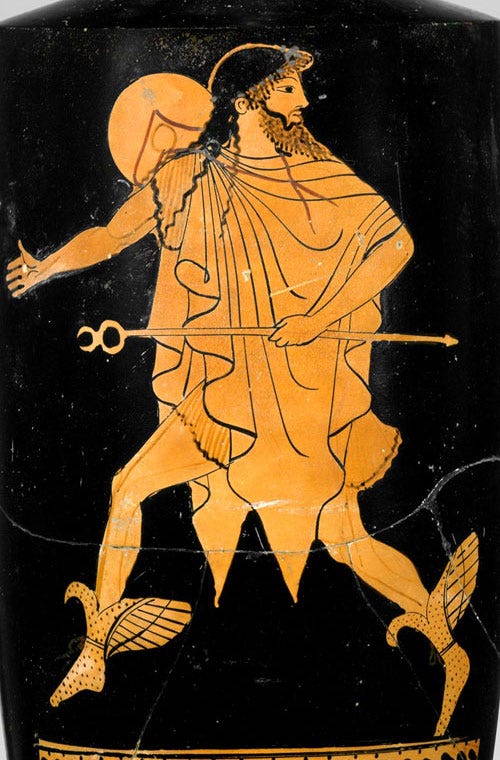

Hermes gadding about

I ask him to tell me a dream and the veteran’s distressed. High colour, heavy set, hands tapping knees, a light sheen of sweat, he’d rather be anywhere but here. But he has no distance left to run. The diets don’t work, the therapy doesn’t work, even the bible isn’t working. Nothing will work because Jeff has a secret. A story. Unsaid words that have been eating him up from the inside for almost fifty years. There was a war in the East that Jeff never came back from. But today, finally, the story’s going to get told. The whole sprawling extraordinary mess of it. In a hut in the backwoods of Minnesota a taboo will get broken. Jeff will say the thing he cannot say. I tell the small group of veterans that we won’t be stopping for supper until the story’s done. Late summer light slants through the window and lands in the circle between us, dust suddenly visible.

Ruth is sitting with her back against a rowan tree in a Dartmoor forest. She’s talking about the rape she endured at fourteen as if it happened to someone else. The Godawful horror’s been told so often it’s taken on a literary polish. I listen and prod the fire. I then ask her to tell the story in a way she’s never done before. Not for the podcast listeners or Ted Talk. Not as a motivational speech about overcoming adversity. No, tell it like a fairy tale. Tell it in the third person. Something unexpected happens when you do that. Something beyond your own imaginative choreography. She tells the story in this way: Once upon a time, at the end of her childhood, a young woman found herself lost in the forest. Suddenly tears fall like rain. She stays with it, gasping and occasionally silenced but valiantly holding the thread. And, at the end, I ask her the old storytime question––and what happened next? Suddenly the earth is ancient and listening closely to her.

I’m driving Gary back to his house on a Plymouth council estate. He’s off drugs, off servicing men behind the bus station, out of the gang his brother runs. But only just, these things being a magnet he keeps floating towards. Sometimes he wants to talk to me about his life, sometimes not, and the change can be in a fraction of a second. Last time we did he threatened to hurl himself into the fast-moving current of a river we were passing. But today’s different, today he wants a story. I tell him a tale about a girl leaving a village for good and not one pair of eyes is on her wishing her well. At this he moans for a bit, rocks a bit, then makes a grab for the gear stick, tries to uproot it from the stem and bring the car off the road. I pull over and he starts pummelling his own head. Get it out of my head, he says. Get the story away from me, it’s in me, I don’t like it, what have you done? This from a young man who watches horror porn and plays war games on an almost hourly rotation. A tiny folk tale has unearthed something in its terrible simplicity that’s gone straight to his heart. That’s me, the girl is me, no one, no one, is looking out for me. I hug him for a moment, and tell him, I am. To get to you, they have to come through me. He cries then opens the car door.

It’s January, and it’s dark. A great blast of freezing air gallops into the car. For a moment he’s lit up under a streetlamp before darting into the shadows. I will never see him again.

As I say, I collect thrown away stories.

I don’t know if I’ve always done it, but I seem to have a nose for unearthing things that people wish to abandon or swerve from. You see there’s no one in this whole wide world that isn’t carrying a story. You could be a president, a yoga teacher, a junkie and you have this one completely unique thing in your pocket. Your story. It may be crumpled like a bus ticket or writ large on tablets of stone, but it’s yours. And god almighty you need to tell it, to rest in it, to find some peace with it. You may realise this at twenty or ninety, but one day you’ll realise it.

The question is, is your relationship to that story transactional or transformational? Is it useful to others?