New Event:

JOHN MORIARTY & SACRED STORIES

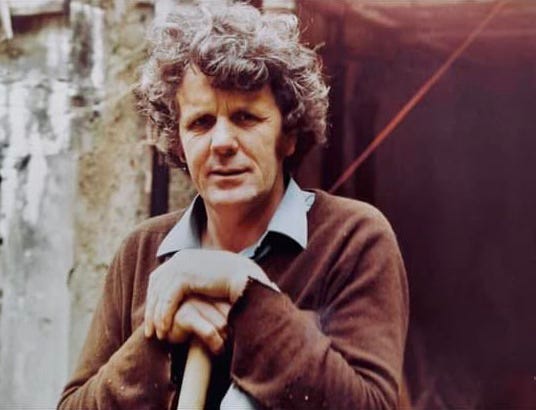

An evening with Martin Shaw

SAT MAY 31ST, KELLS PRIORY, IRELAND

Hello friends - the attached page has a link to tickets. Keep an eye out there for upcoming news of a day workshop led by my friend (and John's niece) Amanda Carmody & Diarmuid Ling. For the evening I will talk about John and his ideas, and tell some stories that would have been dear to both of us. I’m interested in places where he intersects with John Scotus Eriuguna and earlier Christian thinkers.

Here's a link to my introductory book of Johns writings: A Hut At The Edge Of The Village

And the event page: Martin Shaw, John Moriarty & Sacred Stories

THE TROUBLE WITH BEAUTY

The apple of my eye.

The trouble with beauty is twofold at least.

Here’s the first trouble.

That beauty is seen as generic, ornamental and vacuous. That most of us feel anything but. That it’s a long resolved set of ideals that create a hierarchy of value lacking nuance and depth. That at some point, early on, we were exposed to what beauty is meant to be and we came up lacking. Some elitist glitter that makes us hate our own bodies and creates cookie-cutter movies, buildings, clothes and general mindset. It’s beauty not as an inner realisation but a rather vacuous rule of thumb. This is the kind of thing that gets us folding our wingspan to hide our own appearance. It’s beauty-as-tyranny. It’s going to create a long, dragonish tale that it drags behind it.

For it to thrive it has to diminish anything that is-not-it. It’s always hungry because it’s oddly starving.

In the story of The Lindworm we find out that we have an exiled twin, lobbed into the forest the night we were born. Abandoned and marginalised, they grow up in the treeline as we prance about with all the advantages modernity affords us. They watch and glower, grow scales, brood, plan revenge. An interesting reality is many of us have both characters rolling around inside us. So there’s part of us playing the game of vying for affirmation and popularity and there’s a hidden part not buying any of it at all, not for a moment. And we live in the forcefield of these very different outlooks. It can get tiring.

The beauty of the pageant Queen or the chiselled movie star is far too small a definition for anyone with half an imagination. But if those ideals enter the psyche whilst still in its formation – which they will – then we are most likely going to feel quietly lacking. We either shrink away or develop some flighty exterior that flaps above any more grounded appraisal, retinas inflamed with what social media tells us makes us beautiful. This is going to make “beauty” extremely hard to trust. It’s going to start feeling like an untruth.

This is a kind of trouble that it is wise to wake up to. To be un-spelled by. This is not the kind of beauty I’m going to be referring to for most of this essay. The trouble with this definition of beauty is an inhibiting, depressive and constricting form in the world. It’s a grubby enchantment and not to be encouraged.

But there’s another kind of trouble tucked away.

In the story of Tristan & Isolde, Isolde is described as having a beauty that makes other people more beautiful when they behold her. It’s infectious. In Irish stories, Finn MacColl’s friend Dermot is known as having a ‘love spot’ on his face: that when you glimpse him you can’t help but love him. But it’s not to do with him being cute, not really. We all get to glimpse each other’s love spot, when we witness each other doing what we really love. Something cracks open; as diverse as weather patterns or the movement of birds. This is beauty as eruption from the interior not an outer set of visual conditions. Beauty in all its unexpected, diverse and quixotic manifestations.

Maybe it’s Isolde’s harp playing that makes her beautiful, or the spring-bubbling gurgle of her laugh. Maybe it’s Dermot’s skill with a story that makes him so damn attractive. And we leave their company changed, blessed even. We may think we’re in love with them, but it’s likely what’s being transmitted at that moment.

It may be more accurate to say “beauty has them” than, “they are beautiful”.

And here’s the second trouble. Because that kind of thing can bring consequence. An encounter with an Isolde or a Dermot opens a door to both delight and longing. We witness for a moment what stands behind them, that they somehow, stand for. And that encourages us in turn to find out what we stand for, how we will earn our name, what will be our art and skill. To be infected in such a wonderful way may bring the poets’ realisation to our door: that we have to change our life.